Space-Based Data Centers: The Moonshot Worth Betting On

Space-based data centers went from science fiction to a serious investment thesis sometime around 2023. Google, Starcloud, Axiom Space, and SpaceComputer all announced orbital compute initiatives in the last few years. The race is on to scalability, with the finish line somewhere around 2030.

One might say orbital compute is a literal moonshot. And the physics check out:

- Launch costs are declining

- Solar power in space delivers 6x the energy of terrestrial arrays

- Cooling works through direct radiation to the cosmic microwave background.

Every technical objection is being met with a first-principles solution.

So what is stopping orbital compute market from hyper-scaling?

Economics and timelines. They pose a gap between what's technically possible and what's commercially viable. Technical capabilities are now waiting for the market to catch up, and for costs to lower.

We're examining what's real, what's hype, and why the companies positioning now are building for a market that will only take off once launch costs drop another order of magnitude.

What Is a Space-Based Data Center?

Space-based data centers (SBDCs) are orbital compute infrastructure designed to leverage advantages unavailable on Earth: continuous solar power, radiative cooling to deep space, and high security through physical isolation. The architecture varies between massive solar arrays for 24/7 power generation, and constellations for distributed computing. Each architecture offers different compute payload sizes (GPUs, TPUs, accelerators), radiator capabilities, and consensus or communication channels [1].

Dawn-dusk sun-synchronous orbits keep satellites in continuous sunlight by following Earth's terminator line. This results in no eclipse periods, battery cycling, or thermal stress from temperature changes.

Cooling happens through direct radiation. A radiator at 20°C emits about 770 watts per square meter to deep space, approximately 3x what solar panels generate per unit area.

“Cooling in space is simple” is a false statement.

— SpaceComputer - 天机 | 𝕤𝕡/𝕒𝕔𝕔 (@SpaceComputerIO) January 10, 2026

As is “Cooling in space is impossible.”

Cooling in space for space based data centers is a complex architecture problem.

Let's give it some context👇 https://t.co/ZAoGrjicRk

Networking often uses free-space optical links between satellites. Light travels 35% faster in vacuum than through fiber, and there's no intermediate infrastructure to maintain [1]. Connect enough satellites in close formation and you have a mesh network with lower latency than terrestrial data centers for intra-cluster communication.

Patrick O'Shaughnessy captured the vision:

"The most important thing in the next 3-4 years is data centers in space.

— Patrick OShaughnessy (@patrick_oshag) December 9, 2025

In every way, data centers in space, from a first principles perspective, are superior to data centers on earth.

In space, you can keep a satellite in the sun 24 hours a day. The sun is 30% more intense,… https://t.co/3SkUXkPbVv pic.twitter.com/Z2ri4tLSTA

"In space, you can keep a satellite in the sun 24 hours a day. The sun is 30% more intense, which results in six times more irradiance than on Earth. So you don't need a battery. Space cooling is free. You just put a radiator on the dark side of the satellite. The only thing faster than a laser going through a fiber optic cable is a laser going through absolute vacuum."

But first principles solutions for the software and hardware doesn't build the economic promise needed to scale these businesses.

Several assumptions need to hold:

- Launch costs continuing downward from current $1,500-3,000/kg to LEO toward $200/kg or lower [4]

- Commercial off-the-shelf components surviving long enough to finance launch costs [5]

- Thermal management scaling linearly

- Network latency to ground stations acceptable for target workloads

- Maintenance models based on module replacement rather than component-level repair [6]

None of these assumptions have been proven yet at operational scale...yet.

The Physics Reality Check

The cooling objection surfaces in every discussion about space data centers. Armchair engineers veto the entire concept because "you can't cool megawatt-scale compute in vacuum."

Aaron Burnett's research demolished this argument:

if you're an investor and you've heard an armchair engineer 'veto' space data centers because of the radiator/cooling problem, you should read our research this week. 20 mins and you'll have all the tools you'll need.

— Aaron Burnett (@aaronburnett) December 17, 2025

TL;DR - Radiation is a tough engineering problem, but well… https://t.co/CXp3Kz37lo

"If you're an investor and you've heard an armchair engineer 'veto' space data centers because of the radiator/cooling problem, you should read our research this week... Radiation is a tough engineering problem, but well within the physics constraints."

Following the same vein as Starcloud's ResearchThe Stefan-Boltzmann law governs radiative heat transfer:

P = εσT⁴

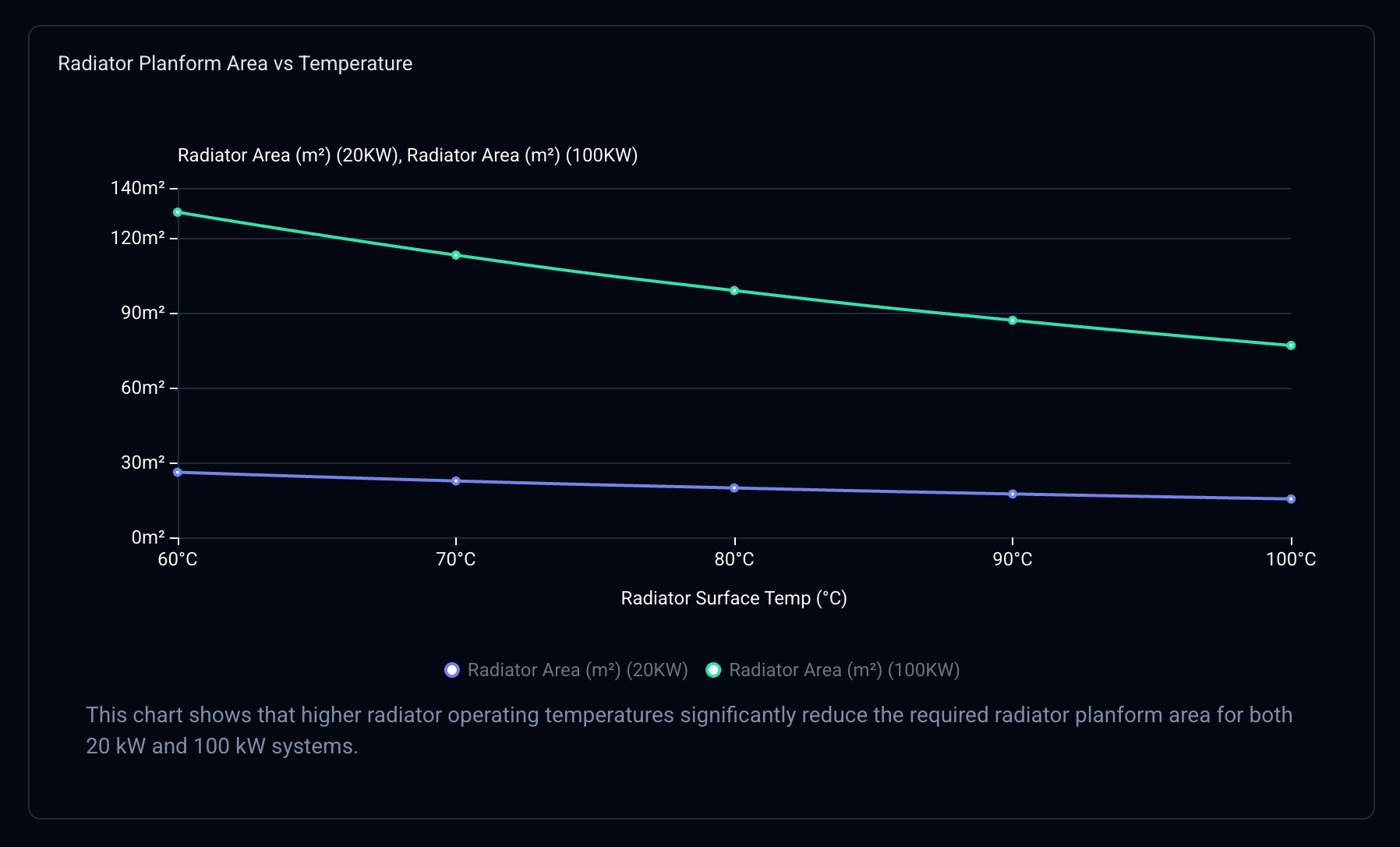

Where emitted power scales with the fourth power of temperature (T⁴ ) [8]. This means the hotter the radiator runs, the more heat it can release per square meter. Small increases in radiator operating temperature drive massive reductions in required area and mass.

Starlink V3 scaling provides the reference case for current centralized architectures [7]. Current Starlink satellites operate around 20 kW for communications payloads. Scaling to 100 kW compute-optimized platforms doesn't require proportional radiator growth. At 100 kW, radiators represent 10-20% of total mass and single-digit percentage of platform area. Solar arrays dominate the footprint.

A 1 m² radiator at 20°C emits 770 watts to space (both sides). That's three times the power density of solar generation. For a 100 MW data center, you need roughly 130,000 m² of radiator area, significantly less than the 200,000+ m² solar array required to generate that power. Starcloud's 5 GW concept renders this visually: their architecture design is dominated by a massive 4km × 4km solar array, with radiators as a secondary system [2].

Mass tells a more complex story. Radiators at 100 kW remain secondary to solar arrays in total mass budget. Pushing toward lighter radiator designs substantially increases cost due to advanced materials and manufacturing [7]. This becomes an architectural choice between mass optimization and cost optimization depending on launch provider economics.

Operating temperature provides the dominant optimization lever. Running radiators at 60°C instead of 20°C reduces required area by more than half due to that T⁴ relationship we mentioned earlier [8]. Heat pumps can boost radiator temperature at the cost of additional power consumption, creating another dimension in the design space.

Cooling is solvable. If you can launch the power generation capacity, you can launch the thermal management system [7].

What Costs The Big Bucks

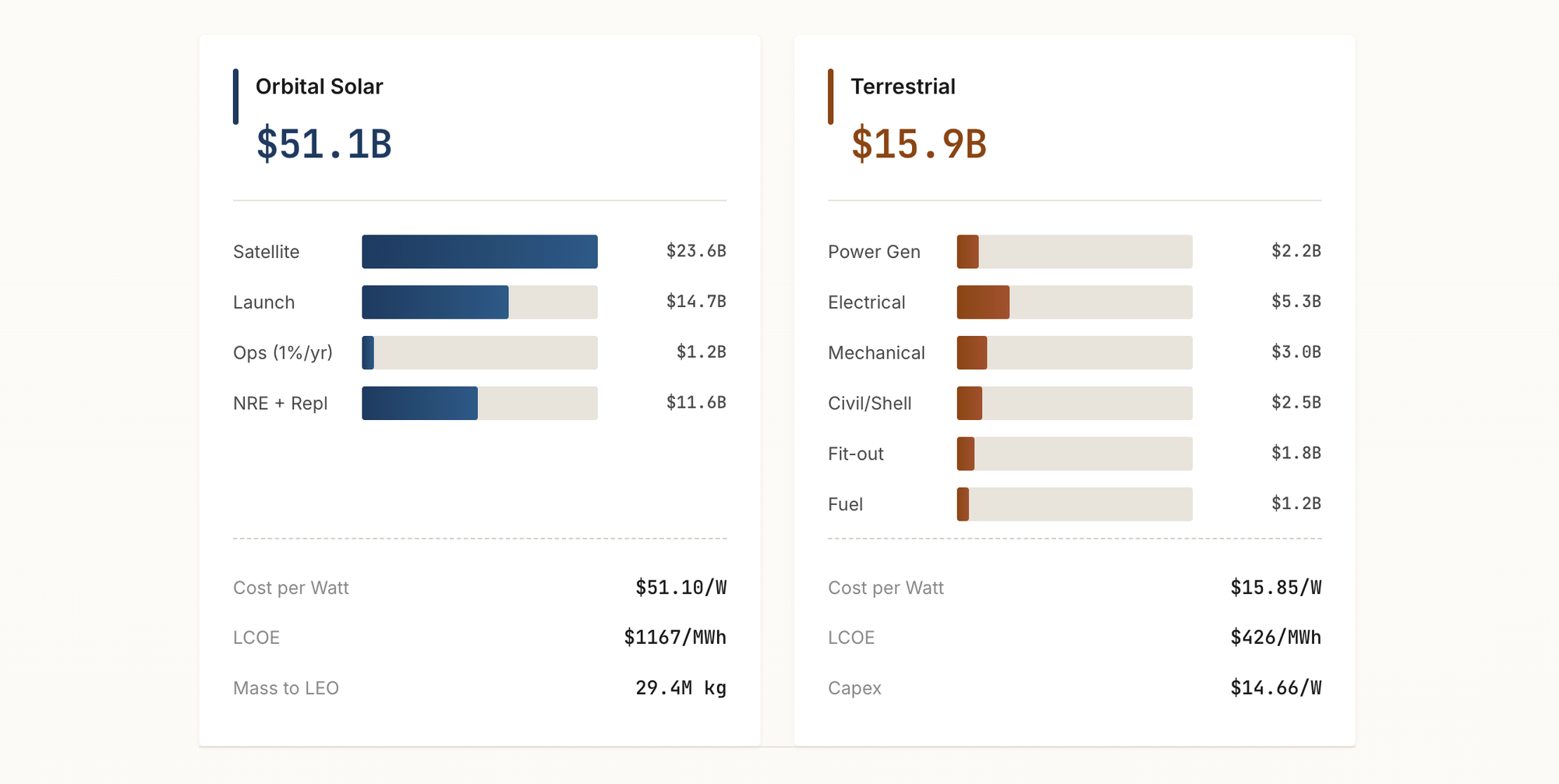

Launch economics currently determine viability of SBDCs. Andrew McCalip's analysis shows current costs at $1,500-3,000/kg to LEO for commercial launches [4]. Even with optimistic mass allocation of 33% compute, 33% power systems, and 33% thermal management, you're looking at 100,000 kg/MW of deployed infrastructure.

At $2,000/kg, launching 1 MW costs $200 million before operational costs, ground infrastructure, or replacement cycles.

The 2030 projection assumes Starship-class vehicles achieve $200-500/kg through high reuse rates and manufacturing scale [9]. At $300/kg, that same 1 MW drops to $30 million launch cost. Still expensive, but approaching terrestrial data center construction costs when factoring in land acquisition, utility connections, and building infrastructure.

Mach 33 Frontier Group's research makes the bull case: orbital compute energy cheaper than Earth by 2030. Their calculation shows space solar generating equivalent energy at ~$0.002/kWh versus $0.04-0.25/kWh for terrestrial power. A solar array in sun-synchronous orbit achieves >95% capacity factor compared to 24% median for terrestrial solar farms in the US [2]. The sun delivers 40% more intensity above the atmosphere with no weather delays or seasonal variations.

Payed over 10 years with $5 million launch costs, a 40 MW cluster could offer energy equivalent to $0.002/kWh [2]. For comparison, wholesale electricity in the US, UK, and Japan averages $0.045/kWh, $0.06/kWh, and $0.17/kWh respectively [11].

Total cost of ownership extends beyond energy:

- Launch financing (dominant cost driver)

- Radiation shielding (1 kg per kW of compute at $30/kg = $1.2M for 40 MW) [2]

- Module replacement cycles driven by radiation degradation

- Ground link infrastructure and bandwidth costs

- Regulatory compliance and orbital debris mitigation

- Zero on-site maintenance capability

McCalip brings a highly relevant counterpoint: cuts to the core issue flexible terrestrial solar beats space until launch costs hit ~$50/kg [4]. Three geographically distributed solar farms eliminate the day/night cycle problem without leaving Earth's surface. You get grid connectivity, physical access for repairs, and the ability to upgrade individual components rather than entire modules.

This viral LinkedIn post laid out the math:

"Let's say you want to launch 1MW into space and you just crush the problems... Your final weight will be around 100,000kg/MW, generating a launch cost on the order of 20MM to 10B… or the same cost of one data center in space, you can build at least three flexible data centers on Earth."

Three terrestrial solar farms in different time zones deliver 24/7 deliver 3x the compute capacity for the same capital expenditure, plus existing grid infrastructure and physical repair access.

The crossover point depends entirely on workload characteristics and launch cost trajectory. Edge processing for satellite constellations makes economic sense today at smaller scales.

With these considerations in mind, general-purpose cloud compute will remain dominant on Earth for the foreseeable future.

Constraints Nobody Wants to Discuss

When you are hearing the hype cycle on orbital compute, there's a few challenges that are rarely discussed...that we've kindly listed below.

Data processing errors and unencrypted communications

What's great about optical links is their speed. What's not great is around 50% of communication happening with satellites is unencrypted. Anyone can easily listen by deploying their own antennas on Earth [24]. This brings forth the question of security of orbital compute data and storage, and how this is tackled in different architectures beyond being physically isolated and tamper-resistant.

Orbital debris

Orbital debris scales with deployment. A 100 MW data center might comprise 50+ separate modules in formation flight. Each module needs active collision avoidance, precision tracking, and coordination with space traffic management systems [6]. The large surface area of solar arrays creates vulnerability to micrometeorite impacts, though ISS data suggests this is manageable over mission lifetime [13].

Hard to access for hardware failures

There is no technician who shows up when hardware fails. The maintenance model relies on module replacement rather than component-level repair. Old modules either de-orbit for atmospheric reentry or get retrieved in launch vehicle payload bays [2]. This works for planned obsolescence but creates challenges for unexpected failures.

Increased Latency

Latency for interactive workloads remains a fundamental physical constraint. A satellite in 600 km sun-synchronous orbit has 4-8 ms round-trip time to ground stations, plus additional hops through inter-satellite links and ground infrastructure [6]. That's acceptable for batch processing and model training, but not scalable for real-time applications serving end users.

Keeping these challenges in mind, it's important to note that these restraints will be solved with time, as orbital comptue is generally a nascent technology, that will mature with the market.

Who's Actually Building This?

Four serious players have emerged over the last two years, each building different architectural solutions with the same set of constraints.

Starcloud

Starcloud is building massive scale, centralized architecture. Last year, they put the first NVIDIA H100 in orbit, and published detailed plans for a 5 GW cluster with a 4km × 4km solar array. Their architecture assumes launch costs will hit projections and that you can launch 40 MW of compute per Starship flight. At that scale, centralized control makes sense if you're operating a single coherent cluster.

The challenge is Starcloud needs everything to work in order to achieve economic feasiblity. Launch costs must hit $200-500/kg. Reusable heavy-lift launch vehicles must achieve routine cadence. Formation flight control must maintain kilometer-scale structures. Any of the assumptions failing or materializing late to the market when it hits commercial feasibility breaks the economics.

Sophia Space

Sophia targets a different use case: edge compute for satellite constellations. Their architecture optimizes for latency-sensitive applications: real-time satellite imagery analysis, sensor fusion, distributed processing of data before downlink.

The architecture uses smaller, distributed modules rather than monolithic clusters. Each module processes data from nearby satellites and forwards results through the constellation's existing inter-satellite links. No need for dedicated formation-flying clusters or massive solar arrays.

Google's Project Suncatcher

Suncatcher represents the most rigorous engineering analysis published to date. Their research explores 81-satellite formation-flying clusters with radiation-tested Trillium TPUs, high-bandwidth optical inter-satellite links, and detailed orbital dynamics [1].

They are doing preliminary research, not announcing a product. But it demonstrates that a tech giant with infinite resources sees orbital compute as technically feasible and worth serious engineering investment.

SpaceComputer

SpaceComputer is building distributed satellite compute platform and trust-minimized interface to connect Earth-based applications to space-based compute resources. Built on tamper-resistant CubeSats with Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) for high-security computations, these SpaceTEEs provide inherent protection from physical access, side-channel attacks, and tampering [15].

We use a novel two-tier blockchain architecture to best high security compute services in orbit: with a celestial Layer 1 and uncelestial Layer 2. The celestial L1 runs consensus adapted for sporadic satellite connectivity and low-bandwidth links through Iridium. The terrestrial L2 handles high-throughput processing with fast pre-finality, confirming transactions in seconds through Earth-based validators, then settling with hard finality when posted to the celestial chain [16].

What makes our architecture work: each satellite is a physically tamper-resistant hardware security module (HSM), and as a network distributed nodes can provide redundancy across independent administrative entities, and smart contracts enable transparent software updates while deterring rogue modifications [16].

The challenges are similar to larger architectures: thermal management, power distribution, latency, and state synchronization across satellites with sporadic connectivity requires novel protocols and specialized hardware for high-security computations.

To combat these challenges, we are developing proprietary software and hardware, and specialized protocols (e.g., the Hotstuff Protocols) to reduce latency.

We will be releasing a paper on the first SpaceComputer-specific secure compute hardware called Space Fabric in the coming weeks.

At SpaceComputer, we are betting on scaling alongside the market and economic feasibility. By offering high security guarantees unachievable on Earth justify the constraints, and the architecture is built to scale over time with increasing constellation size and decentralized network ownership.

The 2030 Horizon

Elon Musk framed the constraint:

Join my conversation with @elonmusk on AGI timelines, energy, robots, and why abundance is the most likely outcome for humanity's future, alongside my Moonshot Mate @DavidBlundin!

— Peter H. Diamandis, MD (@PeterDiamandis) January 6, 2026

(00:00) - Navigating the Future of AI and Robotics

(04:54) - The Promise of Abundance and Optimism… pic.twitter.com/4e4Lstx4ox

"We have silicon shortage today, a voltage step down transformer shortage probably in about a year, and then just electricity shortages in general in about two years." [19]

The energy bottleneck is real, as global data center power demand could triple by 2030 as AI scaling continues [20]. Utilities in Western countries, constrained by planning restrictions and grid infrastructure limitations, can't adapt at the required pace.

Orbital compute will not reach commercial scale by EoY 2026. The 3-5 year timeline for economic viability requires infrastructure that is in the process of being built, but still does not exist yet.

The TLDR on what is required for commercially scalable orbital compute:

- Launch costs must continue declining.

- First-generation systems and Commercial Off-The-Shelf hardware must prove operational longevity.

- Ground link infrastructure must mature.

The opportunity in architectural development is massive, and companies such as SpaceComputer, Starcloud, Sophia Space, and Google are positioning for a market that fully materializes in the next 5 years. The timeline is longer than the hype suggests, which means the industry is on track to making the architecture scalable for commercial and economically feasible use.

This article is brought to you by SpaceComputer.

We are building the accessible distributed compute, storage layer, and the free market in orbit.

Join the mission

Community | Blue Paper | Website | Twitter (X)

References

[1] Agüera y Arcas et al., "Towards a future space-based, highly scalable AI infrastructure system design," Google Research, 2025.

[2] Feilden et al., "Why we should train AI in space," Starcloud White Paper, September 2024.

[3] Patrick O'Shaughnessy, Twitter/X post, https://x.com/patrick_oshag/status/1998440819078898140

[4] McCalip, Andrew, "Space Datacenters," https://andrewmccalip.com/space-datacenters

[5] Bleier, N. et al., "Architecting space microdatacenters: A system-level approach," IEEE HPCA, March 2025.

[6] Eason, Richard, "Mission Design Analysis Methodology for Space-Based Computational Data Centers," University of Illinois, 2025.

[7] Aaron Burnett, Twitter/X post, https://x.com/aaronburnett/status/2001328671320134035

[8] 33 Frontier Group, "Debunking the Cooling Constraint in Space Data Centers," https://research.33fg.com/analysis/debunking-the-cooling-constraint-in-space-data-centers

[9] Liu et al., "Computing over Space: Status, Challenges, and Opportunities," Engineering 54, 2025.

[10] 33 Frontier Group, "Orbital Compute Energy Will Be Cheaper Than Earth by 2030," https://research.33fg.com/analysis/orbital-compute-energy-will-be-cheaper-than-earth-by-2030

[11] Energy cost data compiled from EIA, Grid UK, and Renewable Energy Institute Japan.

[12] LinkedIn post, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/rgfbmn_i-have-been-ignoring-the-buzz-around-space-based-activity-7406805411007430656-HkIZ/

[13] ISS solar array impact data, NASA documentation.

[14] SpaceComputer website, https://spacecomputer.io

[15] Michalevsky, Y. and Winetraub, Y., "SpaceTEE: Secure and Tamper-Proof Computing in Space using CubeSats," arXiv:1710.01430, 2017.

[16] Bar, D., Malkhi, D., Nemcek, M., and Rezabek, F., "SpaceComputer Blue Paper," November 2024.

[17] Starcloud website, https://www.starcloud.com/

[18] Sophia Space company website, https://sophia.space

[19] Elon Musk Interview on Twitter/X, https://x.com/PeterDiamandis/status/2008645261791555859

[20] Liu et al., "Computing over Space: Status, Challenges, and Opportunities," Engineering 54, 2025.

[21] NASA TBIRD mission, 200 Gbps demonstration, 2023.

[22] Vander Hook et al., "Nebulae: A Proposed Concept of Operation for Deep Space Computing Clouds," JPL, 2020.

[23] Axiom Space orbital data center concept, 2025.

[24] Frontier Forum Opening Keynote: Daniel Bar & Filip Rezabek, CoFounders of SpaceComputer https://youtu.be/tZTlQLhnLLQ